Ever since the transformation from impact printing (typewriters, dot-matrix, etc.) to non-impact (ink and laser) took place during the 1980s and 1990s, the dominant technologies of ink and laser have been divided as such. Laser-based technology has always been perceived as more suitable for business environments, and ink is ideal for home and small office environments.

The reasons one technology did so well in a business environment and the other didn't are pretty clear;

- Quality

- Speed

- Archivability

On the other side of the equation, and the reason why inkjet printers became famous in their market segment, was the low cost of entry and the relatively low cost of operation when used in low-volume print environments - i.e., homes.

So, we end up with two different hardware platforms penetrating two distinct market segments, with laser technology relatively concentrated in higher volume output environments (businesses) and ink technology widely dispersed in millions of low volume output environments such as individual homes and small businesses.

As may be expected, the path to market for the hardware and the associated supplies has been quite different for each technology platform, with dealers (resellers) being more critical for laser-based technologies (because dealers generally sell to businesses). Retail is essential for inkjet technologies because consumers visit stores to purchase their devices and supplies.

However, significant technological advancements over the last five years mean consumers have less reason to be concerned about performance differences between the hardware platforms because technology advancements have primarily eliminated them.

This development has set the stage for increased market penetration of the inkjet platform into the business environment. However, it has also introduced a business dilemma for the manufacturers.

At the heart of this dilemma is the fact that hardware manufacturers make money off the printer consumables (ink and toner cartridges) not the hardware.

Laser Technology

The guts of the printer are the cartridges. In having to replace cartridges each time they're depleted periodically, each replacement effectively becomes a "user-managed" preventative maintenance event that extends the life of the printer it's placed into. Furthermore, because the cartridge is a complicated piece of technology, it's been possible for the manufacturers to obtain a broad range of patents that have frequently been used in litigation to help protect market share.

Ink Technology

As with laser, the printer's guts have also historically been the cartridges, with the printhead forming the technological barrier to thwart competitors. Also, as with a laser cartridge, this component of the cartridge has been protected with thousands of patents that have frequently been asserted against aftermarket competitors to help protect market share and discourage competition.

What has changed?

The fact that the inkjet printhead was initially incorporated into the cartridge (not the machine) was one of the fundamental reasons the technology was unsuitable for business environments because it limited the speed of the output.

- This was because the cartridge had to travel left-to-right across the paper before the paper could be advanced.

- Even with machines from Canon and Epson that placed the printhead in the device as early as the 1990s, the printheads were not page-wide arrays, so they still had to travel across the paper before they could be advanced.

Taking the printhead off the cartridge and implementing page-wide printhead arrays eliminates print speed as a constraint. However, the downside is that it eliminates much of the technology barrier faced by would-be aftermarket competitors seeking their share of the downstream consumables revenue.

Aftermarket parties are not interested in competing with the OEM for replacement printhead arrays. This is a highly specialized market requiring enormous capital investments and is a relatively small market compared to the one for the supplies consumed on the devices they're intended for.

What does all this mean for businesses?

As print volumes decline, more and more businesses are questioning whether a $10,000 investment in an expensive multi-function printing device with a monthly print capacity of 25,000 or more pages is necessary. Analysis of actual print volumes may show specific needs to be far lower than these thresholds, a reality compounded with the expectation of further book declines over the machine's lifetime.

Historically, the machine manufacturer and the resellers have controlled the selling process in the higher-end business machine environment. With many buyers routinely cycling from one three-year lease deal into another, they often end up with equipment that's way over spec for their printing requirements. However, more buyers are becoming better educated in these matters and improving their understanding that significant dollars can be saved if alternatives are considered.

Ink-based output devices, having solved the speed, quality, and archivability issues, have become an effective solution for businesses. The fact the underlying technology is inkjet, not laser, is (apart from the stigma associated with its history) becoming largely irrelevant for most consumers, regardless of whether they're in a business or SOHO environment.

Why would a customer choose ink technology ahead of laser?

In accounting for the total (lifetime) cost of ownership, there's less cost incurred to operate an inkjet printer compared to a laser printer which means;

- Ink has a competitive advantage over laser.

- Over time, the ink will win over the laser.

This should be a favorable outcome for consumers (business or home) because they will spend less on the printing device than they've historically been required.

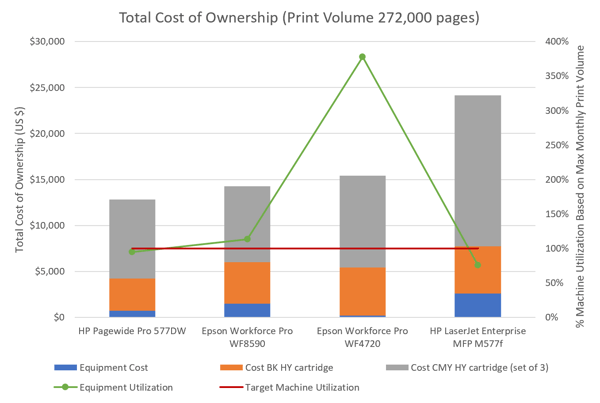

In the case study underlying the example in the chart above, we selected three inkjet printers utilizing page-wide printhead array technology and one laser printer. The study was based on a business with a projected 4-year print volume of 272,000 pages.

- It should be immediately apparent that the three inkjet machines have a much lower total cost of ownership than the laser printer.

- It should also be clear that the Epson WF4720 machine is unsuitable for the projected print volume because it would have to run at an average of nearly 400% of its recommended maximum monthly print volume to handle the expected print volume.

- The HP 577DW and the Epson WF8590 can compete in monthly print capacity with the far more expensive HP MFP M577f printing device.

Hewlett Packard is unlikely to relish the prospect of replacing nearly $25,000 of printer lifetime value (LTV) on its laser device with less than $13,000 of printer LTV on its inkjet device.

However, unless Hewlett Packard placed itself in a position to be prepared to offer an inkjet-based device with a total cost of ownership in this range, it would eventually lose market share to Seiko Epson. So, with little choice but to respond, they introduced their series of page-wide array inkjet printers in October 2012. In doing so, they simultaneously presented their challenge for managing installations in such a way that avoided a stampede out of their laser platform into ink, an outcome which would have served to cut their printing hardware and (over time) their consumables top-line by as much as 50%!

Apart from the potential loss of top-line revenue, what other market share issues arise from page-wide array inkjet printers?

So, this is where it becomes tricky for the manufacturers of page-wide array printing devices.

As we've already mentioned, the lifetime value from a page-wide array inkjet printer can be as much as 50% lower than that from a laser printer.

- The average revenue per unit sold from ink-based output devices is less than laser, reducing the manufacturer's top-line sales revenue!

- Just as with a laser printer, the profits must be earned off the ink cartridges consumed over the printer's lifetime for the OEM's business model to work.

However, aftermarket competitors have fewer technology barriers to contend with on an inkjet output device using a page-wide printhead array than those encountered on a laser-based printing device. This introduces the possibility that the aftermarket may win a higher share of the consumables revenue on page-wide array inkjet printing devices.

The initial sale of the output device only represents a small percentage of the total revenue and profits expected over the machine's lifetime. Should these profits not be realized, the OEM could not continue to invest dollars into their printing platforms, and their technology position would deteriorate. Their business model doesn't work unless the supplies are factored in.

So, the OEM must protect its market share, or its business model collapses.

Why would an OEM, such as Hewlett Packard, introduce a page-wide array of inkjet devices if it increases the risk of loss of market share on the consumables?

As we've mentioned, Seiko Epson could have become (and maybe still could become) a threat to Hewlett Packard with their page-wide printhead arrays should HP have failed to position itself to respond to the challenge. Even though HP knew it could make it harder to protect its market share on consumables, they didn't have a choice; unless they introduced a product to compete with Epson, they would eventually lose to Epson.

Having gone down this path, the challenge becomes protecting market share on the downstream revenue and profits generated by the consumables.

As we've explained, protecting market share was more straightforward when the cartridges had an integrated printhead but, as this changes, it's likely to become more difficult.

In a page-wide printhead array system, the cartridge, now no more than a container of ink costing consumers the equivalent of thousands of dollars a gallon, acts as a magnet for competition. Furthermore, as the most significant barrier to entry (technology) is removed from aboard the cartridge, the threat to OEM market share becomes much more meaningful.

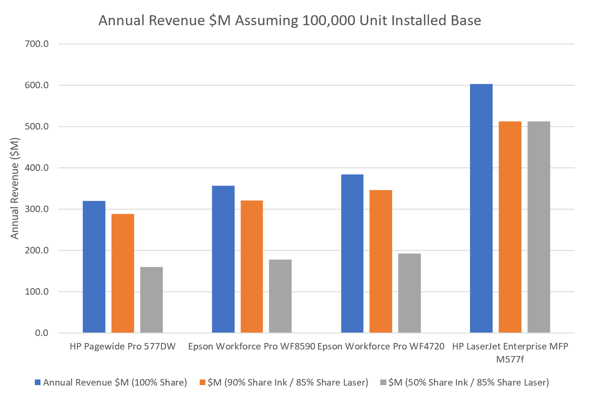

As can be extrapolated from the chart above;

- The lifetime revenue per device is as much as 50% lower for page-wide array inkjet devices than popular laser devices designed to do a similar job.

- The OEMs (including Hewlett Packard) have successfully protected their market share on laser devices - particularly color laser devices.

- If market share cannot be protected on page-wide array inkjet devices, then a decrease from a projected 85% share to 50% (for example) would represent a loss of nearly 70% of the lifetime device revenue and up to 65% of the margin dollars currently earned on an equivalent laser device with an 85% market share.

How do the OEMs plan to protect their market share?

In addition to the tried and trusted methods such as brand recognition, marketing dollars, robust distribution channels, etc., their plans may well center on the increasingly complex chip attached to every cartridge. The chip communicates with the hardware and has been designed so that the cartridge won't function without it. Therefore, aftermarket cartridges must also include a chip that replicates the functionality of the OEM chip while not infringing on any of its patents.

Seiko Epson led the way, adding chips to their ink cartridges in the early 2000s. Others quickly followed, so for the industry as a whole, whether it's an ink or laser cartridge, there's now a chip on almost every cartridge from virtually every manufacturer.

Shortly after Epson's chips appeared on their cartridges, the aftermarket recognized the threat this development represented to their business model; Static Control quickly took a leadership position with its investments in chip technology. They were later followed by prominent Chinese manufacturers such as Apex Technology (now Ninestar). While the chip may have added cost to the aftermarket model, it has not (so far) prevented its continued participation.

Summary and initial conclusions:

We hope we've adequately explained the long-term certainty of the likelihood of a significantly increased market share for inkjet-based systems in the business environment. We hope we've also demonstrated that Hewlett-Packard is well positioned to compete with inkjet-based systems and will use this capability on an "as-needed" basis (for example, when they need to compete on price) to protect and even increase their overall market share. Only "as-needed" because they must wish to avoid a stampede out of their laser platform into inkjet because of the impact such a transition would have on their top line and their profits.

In a forthcoming publication, we will use this foundation to explore how attempts may be made to leverage the cartridge chips and to use them to take on the former role of the integrated printhead as a means to deter the aftermarket and protect the manufacturer's market shares.